Stop Avoiding Conflict. Start Growing Through It.

Most companies treat conflict between teams like a bug that needs fixing.

They’re wrong.

At Auth0, we designed our growth org to create conflict on purpose. Not the toxic, political kind. The productive kind that happens when smart people with different objectives are forced to work together.

The result? Better decisions, better products, and better outcomes for the business.

Let me explain how we did it.

The Real Problem: Two Metrics That Always Conflict

Every company struggles with the same tension:

Retention - How do you keep users engaged with your product, whether they’re free or paid?

Revenue - How do you actually make money from all those users?

These objectives are in constant conflict.

Sometimes, a happy retained user on a free plan starts working at a large corporation. Because of their great experience with your product, they want to bring the paid version to their company. But if you’d pushed them too hard toward revenue early, they might never have stuck around to become that champion.

Other times, you have users who could be paying customers right now, but your retention-focused team wants to keep them in the free product experience to maximize stickiness.

So, how do you make these two conflicting objectives work together?

By getting one team to own retention, another team to own revenue, and then making them fight it out.

How We Structured Productive Conflict

We gave each team clear, different objectives:

Growth Product owns retention. Their job is to make sure people stay and engage with the product, whether they’re free or paid. Everything they do should increase stickiness and long-term value. Conversion to paid isn’t their focus; keeping people using the platform is.

Growth Marketing owns pipeline generation. Their focus is bringing in the right sign-ups and qualified leads and converting them to paying customers. For some accounts, that means self-serve revenue. For big enterprise deals, that might mean routing straight to sales instead of the product.

These objectives naturally create tension. And that’s exactly what we wanted.

Instead of trying to eliminate that tension, we built a process around it:

Before any change ships that affects the user journey, growth product must pitch it to growth marketing. After they build it, before the pull request merges, growth marketing reviews it again.

The rule is simple: they fight until they reach a good idea outcome together. If they can’t decide, the managers step in as tie-breakers.

Before merging the pull request so that the experiment gets deployed, both teams review together the final UI to see if it’s all good.

This isn’t conflict for conflict’s sake. It’s a structured disagreement that forces both perspectives into the solution.

Where the Conflict Shows Up Most: Onboarding (And Everywhere Else)

Onboarding is where this conflict is most obvious. It’s where growth marketing hands off to growth product. It’s where both teams have legitimate input. And it’s where their different objectives collide first.

But this conflict should exist everywhere, not just onboarding.

Example 1: Growth marketing wants to highlight an expensive feature because it drives conversions. Growth product doesn’t want to show it because it’s really hard to use and could hurt retention.

The best outcome? Show it only to people who have demonstrated specific usage patterns and who likely need this feature right now. Target those users. Skip everyone else.

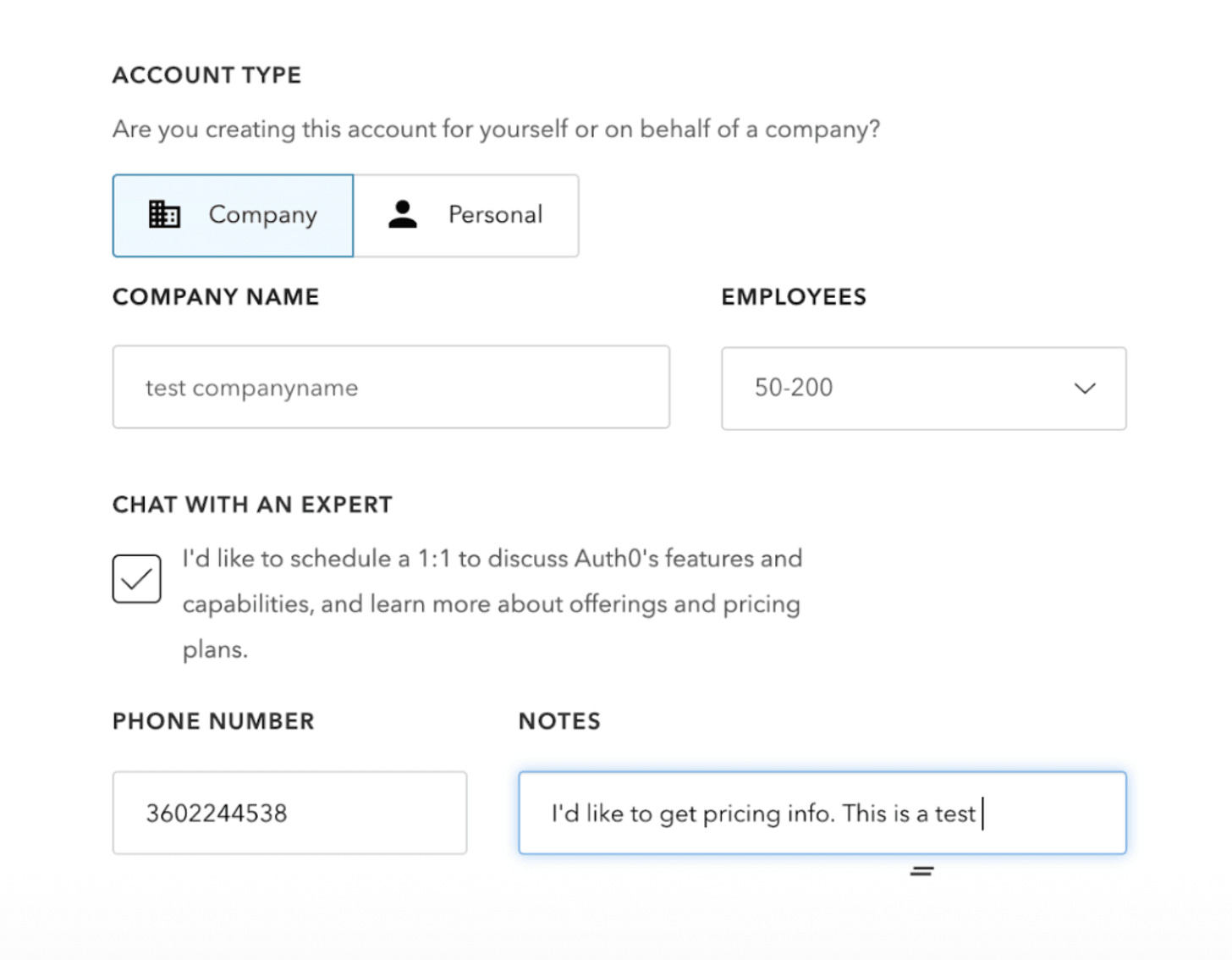

Example 2: Growth marketing wanted to add a checkbox during signup: “I want to talk to sales.” Check it, and you skip the product entirely, straight to a sales conversation.

Growth product hated this idea. Their whole job is retention. If people never experience the product, they never get retained. The checkbox would kill their core metric.

So they fought about it.

Marketing’s case: Big enterprise accounts don’t need to self-serve. A director of engineering isn’t going to be hands-on with the product anyway. Getting them to sales faster is better revenue.

Product’s case: But small company developers absolutely need the product experience. Showing them a “skip to sales” option degrades the whole flow and tanks retention.

They debated. They pushed back. They challenged each other’s assumptions.

And they arrived at a solution neither team would have reached alone:

Show the checkbox to non-developers. If you’re a director of engineering, you see it. If you’re a developer, you don’t.

Show it to people from large companies. Developer from a 3,000-person company? Show it. Developer from a 30-person startup? Skip it.

This was better for everyone. Better experience. Better conversion for the right accounts. Better retention because you’re not forcing the wrong people through the wrong flow.

It wouldn’t have happened without the fight.

The conflict is useful for growth all around. Onboarding is just the first step, but then it’s everywhere: feature visibility, upgrade prompts, email campaigns, product changes. Every touch point is an opportunity for this productive tension to create better outcomes.

Why Structured Conflict Works

When you design for productive conflict, three things happen:

1. Both perspectives get heard. You prevent unilateral decisions that optimize for one metric at the expense of the business.

2. Teams anticipate each other’s concerns. After a few rounds, growth marketing starts thinking about retention before they pitch. Growth product starts thinking about revenue before they build.

3. Better solutions emerge. The tension forces creativity. You can’t just bulldoze your way through; you have to find an answer that actually works for both objectives.

The key is making the conflict structured and productive:

Both teams own their metrics clearly

There’s a defined process for resolving disagreements

Managers are tie-breakers, not first responders

The goal is collaboration through challenge, not compromise through committee

The Bottom Line

Stop trying to eliminate conflict between teams. Start designing systems where teams with different objectives must pitch, review, and challenge each other.

The friction isn’t the problem. Avoiding the friction is.

Build the structure. Define the ownership. Let them fight. Watch better outcomes emerge.

Where in your organization are you trying to eliminate conflict when you should be designing it instead?

You just described the Russian government power structure.