Effective Craziness: The New Growth Methodology

What traits to look for in a top tier Growth Leader

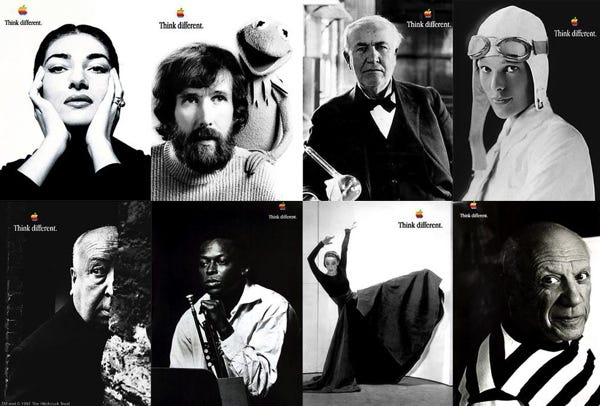

I was 17 when Apple’s “Think Different” campaign hit.

Those black-and-white portraits of Einstein, Gandhi, and Picasso with that unique voiceover: “The people who are crazy enough to think they can change the world are the ones who do.”

Growing up during the Matrix era, when questioning reality wasn’t just philosophy but pop culture, shaped a lot of how I think about growth today.

Twenty-five years later, I get asked the same question weekly:

“What profile should I hire for my head of growth role?”

After working with over 100 companies, I’ve learned that founders are looking for the wrong thing entirely.

They’re hiring from within the same industry, with the same playbooks, expecting different outcomes.

It’s the exact opposite of what Apple did with the iPhone. They didn’t hire from Nokia or Motorola. They hired people who thought phones could be something completely different.

Founders want a marketing leader who succeeds 100% of the time.

I want someone who fails 80% of the time because that’s actually what success looks like in growth.

The person you’re looking for has 3 distinct skills, though they rarely coexist in one individual.

Ideally, you’re finding an effective schizophrenic person who balances insane creativity with a rigorously scientific approach.

The Creative Core: Artists Who See Differently

At the core, you need an artist who sees the world differently enough to generate solutions others won’t attempt.

You’re not hiring a marketer. You’re hiring an artist who happens to work in growth. This person needs to see solutions that don’t exist yet, connections others miss, and approaches that feel uncomfortable to leadership.

A huge part of that art is understanding the buyer at a level most teams overlook. The best growth leaders don’t just generate wild ideas; they land on the right experiments faster because they deeply understand what makes their audience tick. Creativity without that empathy is random noise.

The best growth people I know share something counterintuitive: they’re comfortable with chaos. Not the kind of chaos that leads to missed deadlines, but the intellectual chaos that comes from questioning every assumption. They don’t follow frameworks because “that’s how it’s done.” They ask whether the framework applies to their unique situation and audience.

This is someone who looks at a failing outbound email campaign and questions how to separate the underlying assumptions… Do we have the wrong audience, the wrong message, the wrong offer, or are the emails just not getting through? How do you test those questions? To test out the audience and infrastructure, I asked the following question: “What if we don’t try to get them interested in our product at all?”

That’s the mindset that led me to test telling recipients we had a gift being delivered… intentionally using the wrong address number. Everyone hates dealing with packages delivered to their neighbor’s office. The psychological friction is enormous. The response rate jumped to 12%. Tell me that’s not Art.

Execution Speed: The Angel Investing Portfolio Approach

Creativity without execution is just daydreaming. The second capability is ruthless speed of implementation, someone who can take a wild idea and get it to market before logic talks them out of it.

Of course, this level of velocity only works if the systems are strong enough to support it. Teams that can spin up landing pages in hours and launch outbound campaigns in a day have invested in infrastructure that makes speed possible. Without that foundation, the portfolio mindset collapses under operational drag.

Here’s where the portfolio mindset becomes critical. Most marketing teams run one campaign per quarter and expect it to work. When it fails, they spend months analyzing what went wrong. My teams can run dozens of experiments in that same timeframe because we need signal density to find what works.

Think about it like venture investing. Early-stage investors know 97% of their bets will fail or underperform. But they don’t try to reduce their failure rate to zero, which would mean taking no risks and missing the 3% that generate all the returns. They optimize their portfolio to increase their chances of finding those breakthrough outcomes. Then they double down on winners.

Growth works the same way. That wrong address delivery experiment? It was one of many tests we ran that quarter. Most failed completely. A few showed modest results. That one showed us how to move forward and changed how we thought about that audience psychology. The high velocity angel investing approach made the 80% failure rate the best path to success.

Scientific Rigor: Kill Your Art When It Fails

The third pillar is the hardest: scientific rigor.

All experiments should start with a good hypothesis (why would it work?), a baseline of the current situation (metrics matter), and a rigorous analysis of the outcome.

Good hypotheses rarely appear out of a blank canvas. They come from the exploratory chaos of testing many things, analyzing wins and losses, and spotting patterns worth formalizing. The chaos is not opposed to rigor; it’s the raw material rigor shapes.

This also means being willing to trash your masterpiece if the data says it doesn’t work.

For every growth experiment, I ask three questions:

What psychological principle am I leveraging, and does it match my audience?

What’s the potential lift if this works perfectly?

Is the experiment designed well enough that we’ll know if it failed because of the idea, not because of poor execution or sample size?

If you can’t answer all three, you’re running art projects, not growth experiments. If you can’t answer, DO NOT ATTEMPT the experiment.

At the same time, rigor doesn’t mean dismissing a project too quickly. Sometimes impact is underestimated, or an audience turns out to be more responsive than expected. Home runs are often more impactful than the initial model predicts, so you need space in the system for positive surprises.

The psychological component is crucial because that’s what AI can’t replicate yet. AI can optimize within existing frameworks but struggles with the intuitive leaps that create breakthrough campaigns. Understanding that people hate the inconvenience of neighbor deliveries and that you can leverage it to measure audience quality requires human insight into social dynamics and personal frustration. I haven’t seen an LLM do that yet.

The math (lift & stat-sig estimate) matters because growth is ultimately about scalable impact. That offset delivery experiment taught us our infrastructure worked, and our audience was reachable. We had a product-market fit problem, not an execution problem. Without rigorous analysis, we would have kept optimizing email copy instead of fixing the fundamental issue.

What Success Stories Actually Hide

The problem isn’t finding talented people. It’s that the traditional growth hiring process selects for the wrong traits entirely. Founders look for someone with a track record of “successful campaigns” when they should be looking for someone comfortable with consistent failure (as long as we are learning something).

And they need to create a culture that favors that within their company.

Most growth candidates come with a portfolio of wins and case studies. They’ll show you the webinar series that generated 500 leads or the content campaign that drove a 20% increase in traffic. What they won’t show you is the 50 experiments that failed to get those results, because admitting failure is career suicide in traditional marketing.

But here’s what I’ve learned from working with hundreds of companies: the person who can show you their failures is more valuable than the person who only shows successes.

How to Implement Effective Craziness

The methodology itself requires systematic chaos. Here’s how to structure it:

Phase 1: Hypothesis Generation (Weekly) Your growth manager (the artist) comes up with 10-15 experiment concepts weekly based on psychological insights and audience research.

Phase 2: Rapid Prototyping (48-72 hours) Your growth team (execution specialists per channel) builds minimal viable tests for 3-5 concepts weekly. Landing pages should be done in hours, and outbound campaigns in a day.

Phase 3: Scale the Winners, Learn from Failures (Monthly) Your analyst reviews all active experiments against the initial hypothesis. Kill everything that doesn’t meet the thresholds, regardless of how creative or beloved it may be. The 20% that work get full resource allocation and systematic optimization. But never at the expense of generating new experiments.

This creates a continuous pipeline where creative ideas flow into rapid testing, failed experiments get killed quickly, and breakthrough concepts receive scaling resources. The methodology protects creative risk-taking while maintaining scientific discipline.

The Competitive Advantage of Systematic Chaos

Companies that implement effective craziness methodology create sustainable moats because competitors can’t easily replicate the systematic approach to breakthrough thinking.

When they see your successful campaign, they copy the tactic. They miss the deeper system: the weekly hypothesis generation, the rapid prototyping cycles, the portfolio analysis that killed 30 other experiments to find the one that worked.

Most marketing teams operate in a reactive mode: launch a campaign, wait for results, analyze what happened and plan the next campaign. The effective craziness methodology creates proactive learning loops where insights compound across experiments.

Your artist learns which psychological principles work with your specific audience. Your executor develops templates and systems that decrease time-to-market. Your analyst builds models that predict which experiment types have the highest probability of success.

In six months, this system generates insights competitors can’t access because they lack the methodology to create them. They’re still optimizing email subject lines while you’re discovering entirely new channels and approaches that didn’t exist before.

In a world where everyone has the same tools and data, the only sustainable advantage is the willingness to be systematically unreasonable.

Just like those crazy ones who thought they could change the world… and then actually did.

I would like to thank Noah Adelstein and George Bonaci for their contributions to this content.

This is insightful. Love the idea of sharing failures/ asking about the failure of growth leaders. I'd incorporate that in sharing my work.